We sat down with Andrea Warnick to discuss how to help children with their grief after the loss of a loved one.

She is a nurse, grief counsellor, educator and thanatologist with over 20 years experience in supporting grieving children.

(Thanatologists have undergone advanced study in the phenomena of death and the grieving process.)

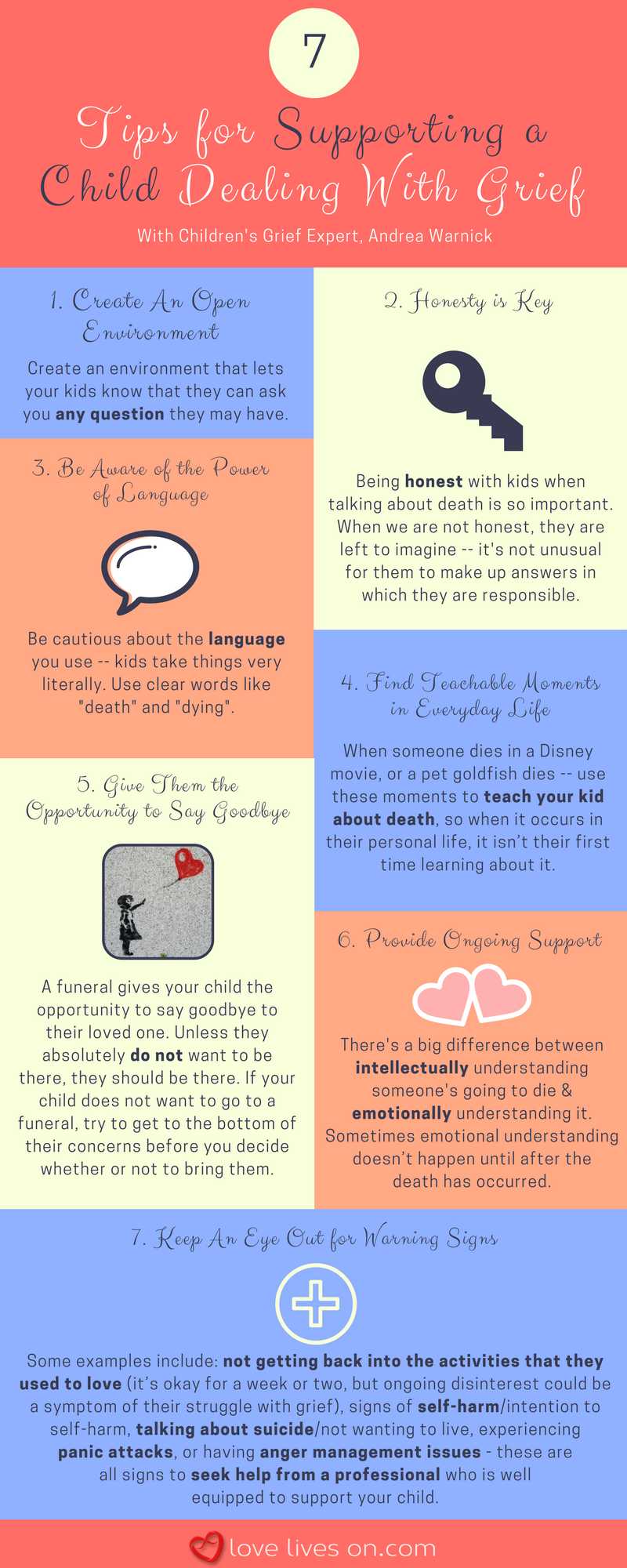

We’ve also summarized some of Andrea’s incredibly helpful tips into an easy-to-share infographic

infographic that you can save to your Pinterest page or share on social media.

Q: How Should We Talk to Children About the Death of a Loved One?

“The biggest piece of advice I can give is to just be honest with kids,” advises Warnick.

“As a society, we really tend to try to shied children from issues related to death and dying, and in both my personal and professional experiences, this does not go over well.”

“When we don’t tell kids what is happening around them, they are going to imagine what is going on.

“If they are living in a family where someone is living with a serious illness or dying and no one is talking to them about it, it is not unusual for kids to make up their own answers in which they are responsible for what is happening.

“They are going to try to put pieces together when they are not given the information.

“So it is really important that parents create an environment where kids can ask any question they may have and that there are no bad questions.

“We might not know how to answer all their questions. Be honest about the questions you can answer and the ones you can’t.

“Just be sure to include them,” states Warnick.

Q: What Strategies Can Help Support a Child who is Grieving?

“Be very aware of the power of language,” cautions Warnick.

“What happens quite often is that parents are scared to use the words like ‘cancer’ or ‘dying’ when speaking with their children, and instead use euphemisms or phrases like ‘mommy is sick’.

“What is often not realized is that this can be very confusing for kids, especially younger kids.

“Their experience with sickness is the sickness that goes around the daycare where one person gets sick and then another and another and they can’t distinguish this kind of sick from sickness like cancer.

“So the next time they get sick, they can’t decipher that the same thing isn’t going to happen to them.

“So when I work with kids, I make sure I am very clear and say, ‘No, mommy has cancer’.

“This is different from the flu or the cold. You can hug her and kiss her. You’re not going to get cancer. [This type of language] emphasize that it is not anybody’s fault.

“Even with death and dying, parents are afraid to use the words ‘death’ or ‘dying’, so they say things like ‘passed away’ or ‘passed on’.

“Older children usually get what is meant by this, but younger kids don’t understand.

“Some parents say, ‘Grandma is sleeping,’ or ‘She went for a long sleep’.

“This can be terrifying to kids.

“Even very well intended things like, ‘Grandpa will always be in your heart’, can be misinterpreted.

“I’ve worked with kids who were scared because they actually thought Grandpa was in their heart.

“Kids take things very literally and concretely, so it is important when talking to young kids, use the words ‘death’ and ‘dying’.

“I suggest taking everyday situations, like a dead squirrel on the sidewalk, and turn them into a teachable moment with your kid about death.

“Instead or avoiding it and walking around it, use it as an opportunity to teach your kid about death when the death is not a highly emotional experience.

“’This is a dead squirrel. Its body doesn’t work anymore. It doesn’t feel hot or cold or any pain. Its body will never work again.’

“When someone dies in a Disney movie, or a pet goldfish [dies], use those moments to teach your kid about death, so when a death occurs in their personal life, it isn’t their first time learning about concepts related to death,” advises Warnick.

Q: Should our Support Strategies Take into Account the Manner of Death?

“How does your approach to supporting a child who is grieving the loss of a loved one due to illness differ from how you support a child who has lost a loved one with violent death, like an accident, suicide or crime?” asks interview host Courtney Murdock.

“There is more shock involved in a violent or unexpected death of any kind, so it can take a long time to help kids, (as well as adults), wrap their head around what has happened,” responds Warnick.

“Yet, even when I am preparing kids for an expected death, I’m aware that there is a big difference between intellectually understanding someone is going to die, and emotionally understanding it.

“Sometimes that emotional understanding doesn’t happen until after the death has occurred.

“I’m very, very conscious in the families that I work with when someone is dying in their family that we use the time leading up to death to prepare the kids well because what we do with them leading up to that death really changes the story of how the child will grieve that death for the rest of their life.

“My hope is that when a child goes through that heartbreaking experience of losing a loved one, they don’t come out of it feeling as though the adults in their life knew what was going on, but didn’t tell them about it, or that they were lied to.

“And then they can have trouble trusting the adults in their life.

“Even though withholding the truth is well-intended and done out of love and protection for the child, it can actually backfire and feed into the child’s anxiety following the death of a loved one because they feel as though their family doesn’t tell them about things that are really hard.

“When it is an expected death, I’m really going to do everything I can to make sure that the child feels included, and that they have the chance to say goodbye to the person, and all of those pieces.

“When death is unexpected, this looks different, but a lot of those pieces are still really relevant.

“How do we say goodbye to someone who is not physically here?

“How do we stay in relationship with someone who is not physically here?

“There are elements of those pieces that are the same,” advises Warnick.

Q: Should we Take Children to Funeral Services?

“Many funeral directors that we have worked with have mentioned that most parents do not bring their children to a loved one’s funeral or memorial service in order to protect them from the pain associated with death and grief.”

What are your thoughts on this?” asks Murdock.

“I absolutely encourage families to bring children to funerals,” answered Warnick.

“In a Harvard study that I have read concerning the impact of a child’s participation in a funeral service for a sibling, the results far and wide demonstrated that their participation was actually a helpful thing and incredibly beneficial.

“My experience in my own work is the same.

“If children want to be there, they should be there.

“Even if they don’t remember being there, the fact that they were there becomes part of their story.

“Especially if it is anybody that they have a close relationship in their life, they will ask one day if they were there.

“Having said this, if there are kids who absolutely do not want to go to a funeral, that’s a different story.

“What I would advise here is to get to the bottom of their concerns.

“Especially with teens and tweens. Is there is something that they are actually scared of emotionally about the funeral service, or do they do not want to go to the funeral because they would rather be doing other thing?

“I advise parents, (obviously when it is possible), to bring their children to funerals they are attending that maybe do not carry a heavy emotional experience for the child, (such as a great aunt or a neighbour down the street), so they can experience it when it is not such a personally emotional experience.

“I prepare a lot of kids to attend funerals and just try to address what they can expect at a funeral.

“I always say, ‘So and so’s body will be in the casket,’ (if that’s the case). ‘You can touch the body. It might feel cold and hard, but that’s okay. You won’t get cancer (or whatever the illness was) from it.’

“I have had kids come back to me saying, ‘Andrea, you said that the body was going to be there, but the head was there too!’

“So I learned that kids take things very concretely, and think of the body as [being] from the neck down.

“So this is an example of why it is important to have these conversations with kids leading up funerals about their fears, so we can know these fears and address them.

“Discuss these fears and answer their questions, and then see if they are still reluctant to go.

“If, after this, the child is still really uncomfortable and doesn’t want to go, don’t bring them.

“But try to do some other kind of ceremony to give your child the opportunity to say goodbye because the child will benefit greatly from that experience,” explains Warnick.

Q: When Does a Grieving Child Need Professional Counselling?

“What signs should parents and guardians be looking for that might indicate a child needs professional grief counselling in order to deal with the grieving process?” asks Murdock.

“That really depends on what the relationship the child had with the person who has died,” advises Warnick.

“If somebody really close to the child died such as a parent or a sibling, if parents have the resources, I encourage parents to seek the help of a good grief counselor for even a couple of sessions.”

“So many kids feel that they are responsible in some ways and have misconceptions about death.

“Just like parents want to protect their kids, kids actually want to protect their parents.

“So especially in cases where the parents are grieving a loss as well, kids may not ask all of their questions, so talking with a grief counselor about these questions can be really helpful.

“Of course, not everyone has the resources to connect with a children’s grief counselor or children’s grief support group. And not all communities have counselors or programs with expertise in children’s grief.

“So my advice here would be to keep an eye out for things such as if the child is not getting back into the activities that they used to love.

“It’s okay for a week or two, but after that, if they are still showing no interest, this could be a symptom of their struggle with grief.

“In addition, signs of self-harm, or the intention to self-harm, or if you child talks about suicide, or not wanting to live, or if they are experiencing panic attacks, you automatically want to seek help from a professional who is well equipped to support the child.

“Another warning sign to look out for is anger management struggles.

“For a lot of people who are grieving, it is easier to be mad than sad.

“So it might be that the child is lashing out a lot, and this can be rooted in grief.

“So again, my advice would be to seek help from someone well equipped to support the child, if possible.

“I also advise parents to seek coaching help from a grief counselor so they themselves can get equipped with the skills necessary to offer support to their child,’ advises Warnick.

(Click infographic to enlarge)

Like our infographic? Use it on your site by copying this code:

Know that You’re Not Alone

Andrea Warnick has so kindly shared her expertise in supporting children who are dealing with grief after the loss of a loved one.

We look forward to reading any feedback or questions that you may have in the comments section below.

Please know that you and your family are not alone. Love Lives On is committed to providing you with resources and tools to help you in your time of grief. We are truly sorry for your loss.

To find a grief professional or support group in your local area, search our vendor directory.

You can also follow our Pinterest board for more resources for supporting grieving children.